French photographer Ronan Guillou has been panoramically surveying the US for some 20 years through the lens of his Hasselblad camera. Highlighting fragile figures and topographical decay, he examines — and undercuts — the vast myths grafted onto the American territory. It’s a place he has been fascinated by ever since he saw Wim Wenders’ arid, wistful film Paris, Texas as a teenager (Wim would write the intro to Ronan’s photography book, Angel, years later). Ronan’s observational gaze uncovers melancholic beauty in the margins.

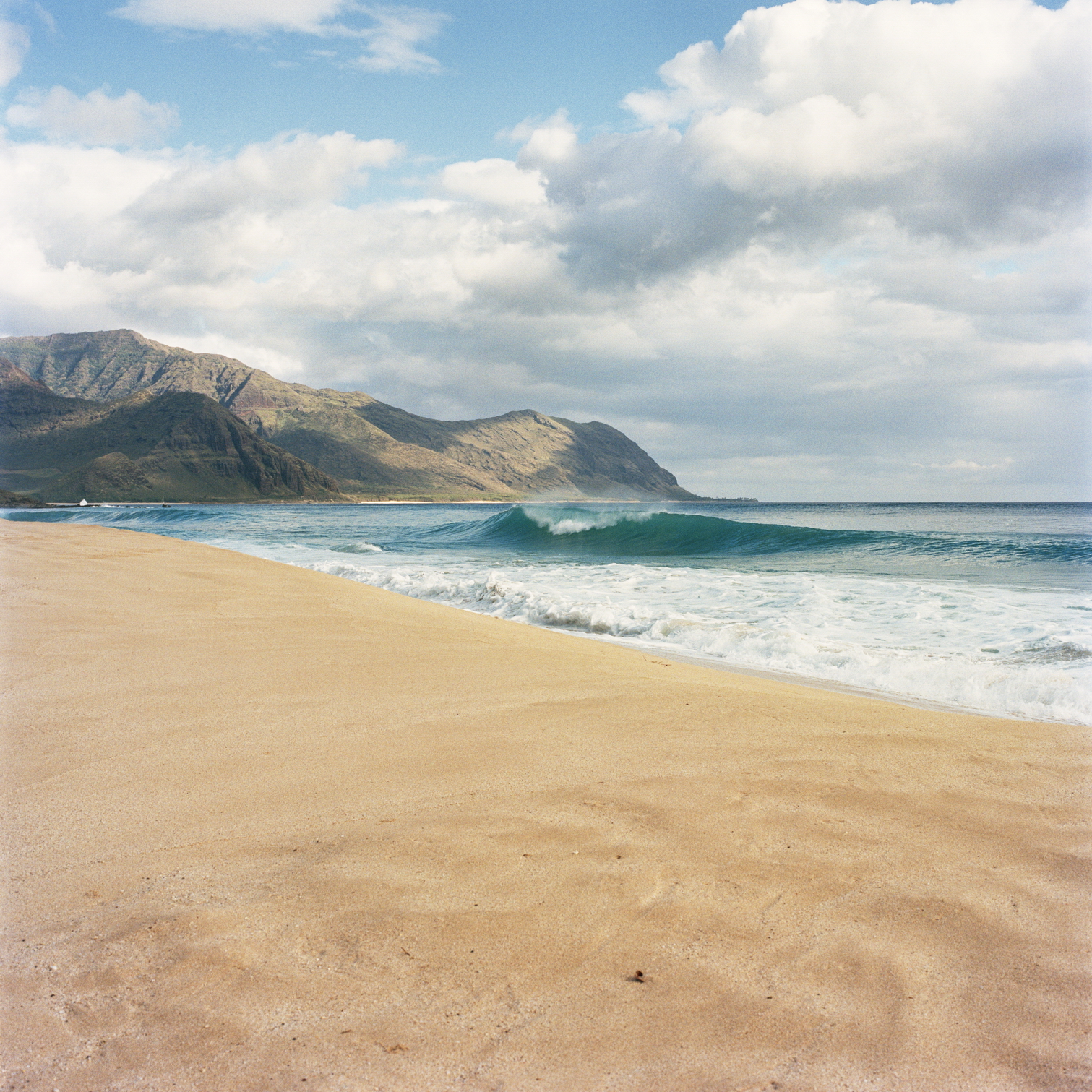

His series Paradise (2016-2017) is part of his long-term project American Narratives, but remains distinct from it. In the middle of the North Pacific Ocean, more than 130 islands form the state of Hawaii: a photogenic cluster that is nonetheless underrepresented in the American photographic tradition. His images of this region are part of Festival Photo du Guilvinec in France (June 1-Sept 30), which spotlights ocean-themed photography as a subject and locus. The exquisite light, sublime shoreline and spirit of serenity evoke otherworldly dreaminess, but Ronan was conscientious to not project a clichés Elysium.

Far from the ocean (but next to Paris’ Canal Saint-Martin), Ronan spoke about the trials of depicting an idyllic setting, the liberal access photography enables and veering away from both déjà vu and exoticism.

What has drawn you to America so regularly?

When you’re interested in a territory, you have to explore it as far as you can. I’ve been interested in America, and in American photography as a genre, for some 20 years. The reason I wanted to work in Hawaii — following work I did in Alaska — is that few photographers have shot there. It’s as if they’re separate countries. Alaska is the largest state, but I couldn’t find any references from major photographers… aside from Ansel Adams, who documented landscapes.

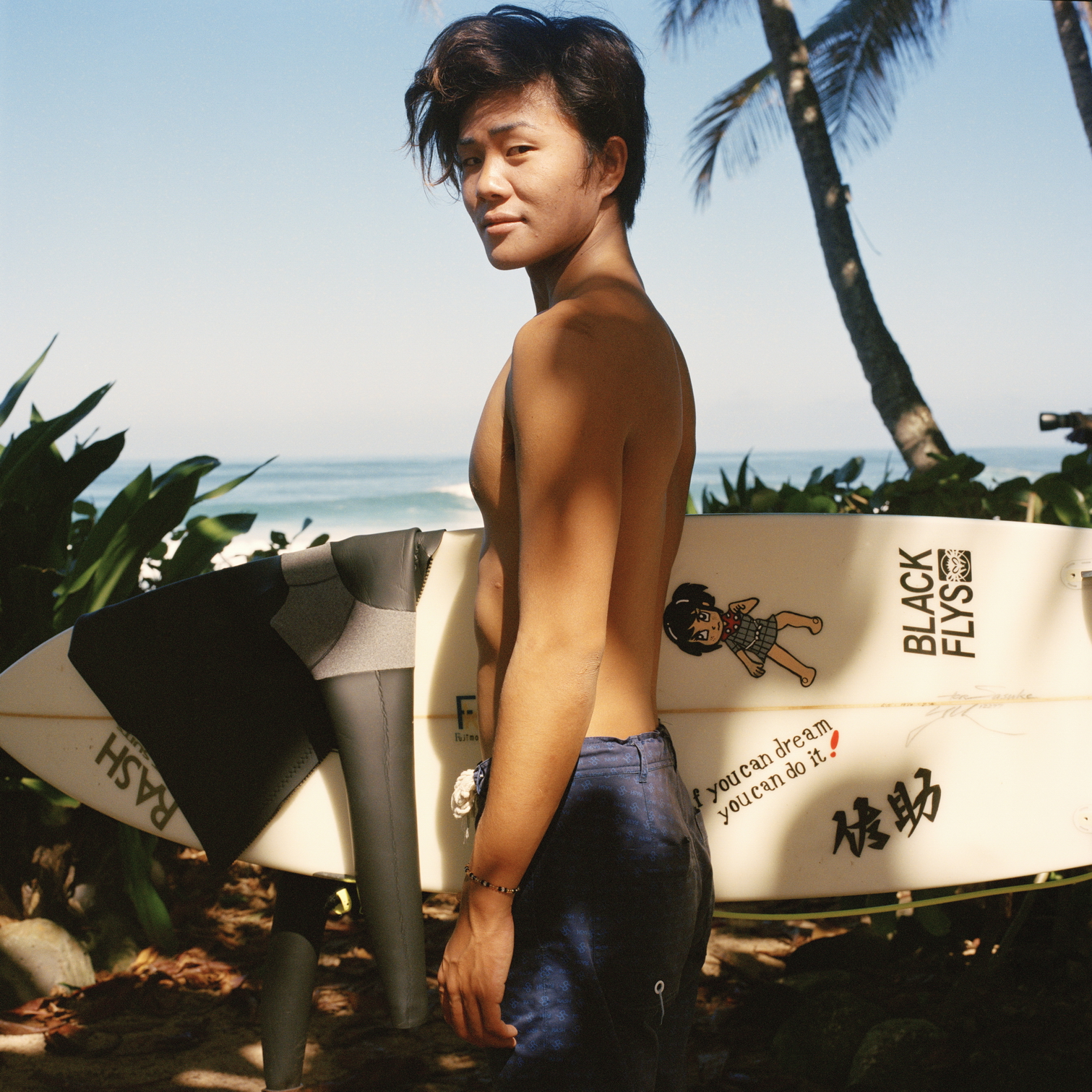

Hawaii is the far west of the US, and has a different history, an insularity. I went to one island, Oahu, for one month three times apiece. There are commercial hotels, lots of Japanese weddings in Honolulu and surfer culture is so present you can’t avoid it. But all the identifiers of America disappear. No billboards, no wide open spaces and the populations are different. I asked myself: when all the signifiers and contrasts disappear, does the American Dream exist?

What were the challenges of photographing this particular context?

From a photographic viewpoint, we expect to encounter a kind of tension. But in paradise, there’s no tension. Or if there is tension, you can’t render it visually. I took the least amount of photos here, relative to other places, because of the pitfalls of vacation photography and “easy” images. It was tricky to find small details that felt out of the ordinary. And I didn’t want to take Martin Parr photos either, where everyone is photographing each other or taking a selfie.

In paradise, everyone seems happy. And happiness gets on your nerves, after a while [laughs]. Even people who had no place to live slept on beautiful beaches — while that’s hard, the backgrounds are still stunning. It’s very strange!

Do you consider this project ongoing?

Photographing the US is a long-term project for me: I’m fascinated by the country. Truly. Because it is full of contrasts, paradoxes, oppositions. Progress and conservatism. I’ve worked on projects examining the social and economic margins that show the difficulties for people who haven’t attained the American Dream. That sector is rife with tension.

Is there a particular way you’d qualify your photography?

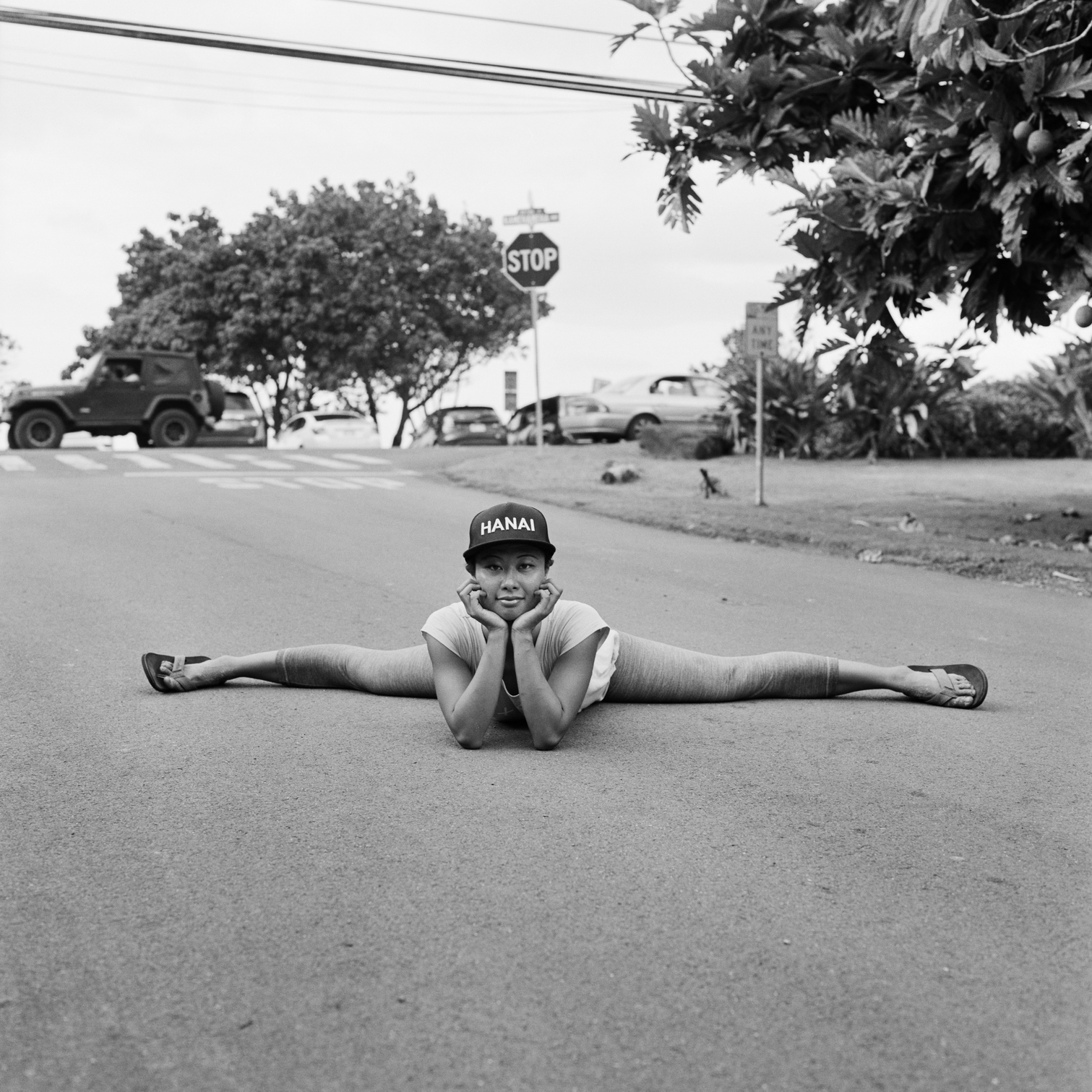

I call it “experience photography,” which is linked to what I feel through places, people, forms, color, composition. Photography is about your casting process, based on who you meet. I can be at a church at noon and in the woods with hippies in the evening. I like the idea of an open-ended practice. I think of it as a corpus of impressions. I don’t like to restrict myself; I like to open every door. I’m always interrogating.

But I don’t have a protocol; I follow my intuition. I can stay three hours just observing. And when I chat with people, they advise me on what I should check out, and I do. I improvise, and other people shape my story. Photography is a way of unlocking others. What I remember is people’s generosity in sharing themselves.

How do you approach people?

It varies from person to person. Photography can be invasive, but it can also show that you’re interested in people. Some people I spend half a day with, follow around, see again… not even to photograph right away, just to spend time with them.

The man with a beard is Kawika. He was one of three surfers coming out of the water, and in this specific light, I had a kind of photographic revelation. I said to him: “May I take your picture now and I’ll tell you why afterwards?” I took three photos — I work with an analogue camera, a Hasselblad — then I introduced myself, and asked if he wanted to speak about himself. For a half-hour he told me — a complete stranger! — about his drug problem, his connection to Christ, his relationship with his mother (who is Hawaiian, while his dad is of Irish heritage). He cried several times over the course of the conversation. He himself has such a Christ-like look.

I also met some master tattooers who practice ancestral hand-tap tattooing, using a stick with pelican bones at the ends. They sit on tatami mats, surrounded by assistants, creating ethnic designs. I went over without my camera; I spoke a little, but mostly listened. It required being present, not just taking a quick photo in passing.

Nowadays, it’s unlikely I’ll see these people again; we only exchange via social media. So it’s ephemeral, but still sincere and meaningful. We like each other’s photos as a way to communicate a “petit bonjour.”

What is the advantage of having a foreigner’s eye?

I’m a foreigner, but I know the US well. I’d call myself more of a “passenger” than a “foreigner.” I like “passenger” as a concept because it gives me the chance to meet alternative people, to extract myself from my comfort zone and go where I wouldn’t have without photography — to experiment and explore.

But examining a culture that’s not natively yours liberates you from certain constraints, no?

It is always an advantage to have a different point of view and to ask different questions. But I don’t know if it’s being a foreigner or being a photographer that frees me from constraints.

Regarding analogue, can you elaborate on this choice of material?

The appearance of my camera can create a link because it’s vintage. It’s a beautiful object; people are curious about it. And I use a light meter. I use it less for the result than for the way I work with it. I don’t need batteries; I’m autonomous. It’s another relationship to “photographic time” — it makes you selective, it channels your energy into a form of contemplation. That motivates me. I’m not against digital, or some kind of artistic conservative! It just pushes me towards another way of operating: I look differently, and think about temporality differently.

I can’t look at what I’ve done over the course of the day; I just move on to the next thing. I don’t have to backup. I don’t have to show the subject what has been done. I let the undeveloped rolls of film accumulate. It’s all a mystery that reveals itself to me later. It’s about rediscovery, and it’s a bit magical.

More Stories

Beach Volleyball falls to Long Beach State in Big West Championship

Hawaii’s Hill, Long Beach State’s Valenzuela eager to match wits

Hawaii blocks some Waikiki sands for seal pup