Taken from inside a cave at Kalalau Beach, Kauai.

Kevin Boutwell/Getty ImagesRemote valleys in Hawaii have become far and few between, but in the 1950s, when Dr. Bernard Wheatley wandered from Europe to the U.S. and, finally, to Hawaii, he found isolation in what is now the Napali Coast State Wilderness Park.

Wheatley began living in Kalalau Valley in 1957, when he was about 38 years old, living off of taro, fruit and fish. He became known locally and nationally as “the Hermit of Kalalau.”

It was an unlikely move for a man who had been a brilliant student and doctor, according to those who knew him.

Wheatley was born in 1919 in St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, one of 10 children. He “graduated from Meharry Medical College at the top of his class” in 1945, but because of racism — Wheatley was Black — he was rejected from a top Boston hospital despite earning the highest score during the application process, a December 1959 Ebony Magazine article reported.

“This was the real blow that crushed him,” said Dr. John W. Parker, a Brooklyn surgeon and Wheatley’s college roommate, according to the article. “He had a different outlook after that. He simply lost interest.”

Wheatley began practicing in Sweden after a return to the Virgin Islands. But just six years later, for reasons that are still unknown, he left his medical practice, gave away all his money and personal belongings and arrived in Hawaii.

Wheatley’s home became a large cave on the beach, at the end of the Kalalau Trail, about 100 yards wide and 40 yards deep, which he kept impeccably clean.

In the 1950s and early ’60s, Dr. Bernard Wheatley found a home in a cave (far right) on Kalalau Beach at the end of the Kalalau Trail.

Westend61/Getty Images/Westend61

Located on Kauai’s Napali (the cliffs) coastline, the Kalalau Trail weaves in and out of five valleys and along the cliffs’ edges high above the sea. The trail is most widely known for its first 2 miles to Hanakapiai Beach, but backpackers with permits can continue to Kalalau Valley and its beach — including the cave where Wheatley lived — at the end of the 11-mile trail.

Native Hawaiians lived in the Napali Coast’s various valleys, and remnants of this history can still be seen today, such as rock wall shelters found in Hanakapiai Valley, agricultural terraces in Hanakoa Valley, and heiau (traditional Hawaiian place of worship) situated on cliffs. The Kalalau coastal trail wasn’t built until the 1800s, and Hawaiians largely traveled the coast by ocean in a canoe or by land, climbing over the cliffs.

It’s believed Hawaiians left Kalalau Valley in the early part of the 20th century. From then through the 1950s, it was a largely uninhabited coastline.

“People may think I am a fool,” said Wheatley, in a 1961 Honolulu Star-Bulletin article, “but I have found real happiness and above all real peace of mind in the valley.”

There are conflicting reports about why Wheatley left his life behind to become a hermit. A heart attack in 1951 may have caused him to take a “long look at his life,” Ebony magazine reported. Another report says that he had lost “his wife and son in an automobile accident.”

When he arrived in Hawaii, Wheatley didn’t immediately hike to Kalalau. He lived in a Honolulu hotel, without means of support or a way to pay his hotel bills. He was arrested and jailed, until someone paid them and he was released.

“My guess,” a friend of his said, according to Ebony magazine, “is that these experiences are what finally drove him out of the world and into Kalalau. To a man of his sensitivity, I should think an arrest and appearance in court with attendant publicity would be a sort of final stamp of social disapproval in his mind.”

Whatever the reason, Wheatley talked of his time in isolation as a time for thinking, writing and immersing himself in the teachings of Christ. He was also vocal of his disdain toward modern society and medicine.

“He says the delights he found in civilization were bitter, the men he knew were dull and the medicine he practiced was spurious. He says the legendary Kalalau Valley is the only place he has found where a man can be honest 24 hours a day,” Ebony reported.

“On the outside,” Wheatley said, “I constantly feel limitations around me. The instinctive reaction to a new situation is fear. There is so much that is negative in the world, so many people say, ‘That’s impossible.’ Here in the valley I feel no fear or limitations. … Here there is more than just quietness. There is a big peace.”

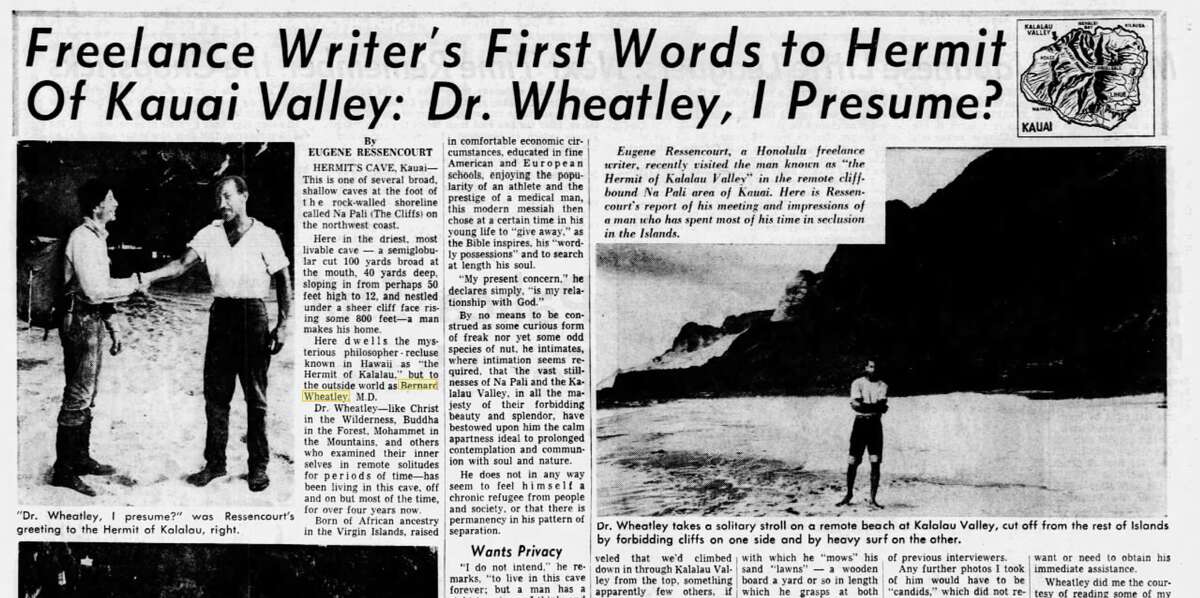

People would hike the Kalalau Trail to visit Wheatley on occasion. In this instance, the writer hiked over the cliff from Kokee.

Newspapers.comThe peace that Wheatley sought did not last forever. Media attention inspired people to trek out to the valley and visit him. He lived in the valley on and off for about four years, leaving in the early ’60s because it became too crowded, especially as hippies and other would-be hermits began to move in. After leaving the valley, Wheatley traveled between Hawaii and the continental U.S. and back to Kalalau Valley for short visits, continuing to live a simple lifestyle.

He completed two books in the late ’60s, a volume of poems, “On a Clear Day,” and a group of essays, “A Spotlight on Life.” In 1969, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported Wheatley was also working on a book about “health and metaphysical orientation” and another about his life in the valley.

Wheatley died in 1991 at the age of 72, living elsewhere on the island of Kauai. His friends carried his ashes over the Kalalau Trail to Kalalau Valley where they were spread.

The book about his life story remained unpublished and incomplete at the time of his death, according to a 1992 Honolulu Star-Bulletin obituary.

“I did not shrink down into loneliness,” he wrote in one passage of the autobiography he had planned to call “The Needle’s Eye.” “I felt my entire being reach out on all levels of consciousness to touch with love and appreciation all of the beautiful, magnificent, powerful entities which were deployed in profusion about me: the ocean, the cliffs, the untrodden, rippling sandy beach; the planets, the stars, the moon; Omar Khayyam’s rising sun coming over the high ridges (catching God’s turrets in its noose of light) and the incomparably beautiful, deep, peaceful sunset; the crystal clear, refreshing bubbling, cascading mountain streams; the intriguing waterfalls; and the literally fruitful green forest.”

More Stories

Beach Volleyball falls to Long Beach State in Big West Championship

Hawaii’s Hill, Long Beach State’s Valenzuela eager to match wits

Hawaii blocks some Waikiki sands for seal pup