The Coronado Motel, formerly known as the Coronado Lodge, was a place listed in the Green Book as a place that welcomed African American travelers. The motel, located in Pueblo, sat on the pages of African American travel guides for a decade, and remained one of only three Colorado motels to be listed through 1967. (Video by Skyler Ballard/ The Gazette)

The owners of the Coronado Motel in Pueblo don’t spend on advertising.

Guests who stay at the lodge return, charmed by the historic Pueblo-style building.

Maybe it’s the thick, adobe walls or the wood-beamed ceilings. Maybe it’s the bell tower or the life-sized bear carvings.

You can tell it’s loved by a whimsical touch. Little hints of colorful artwork appear throughout the motel, along with a mural painted on the courtyard’s back wall.

It might even look familiar — the motel made a guest appearance in the 1983 cult-classic “National Lampoon’s Vacation.”

But, it holds a more important history — one that Colorado researchers are trying to preserve.

A plaque for the National Register of Historic Places is near the entrance of the Coronado Motel, formerly known as the Colorado Lodge. The lodge was a place listed in the Green Book as welcoming African American travelers when many other hotels would turn them away. Thursday, Feb. 8, 2023. (Photo by Jerilee Bennett, The Gazette)

It wasn’t until March 2020, that the midcentury motel was accepted into the National Register of Historic Places, after local historians worked to uncover its story.

The goal: highlight a history that has long gone ignored, part of a larger movement from historians across the country to preserve historic spaces relevant to underrepresented communities.

The Coronado served as a safe place to stay for African American tourists during a time when few establishments did.

The Coronado Lodge, upon its first listing in 1957, became just the second Colorado motel to be mentioned in “The Negro Motorist Green Book: 1957” — an annual guidebook for Black travelers during the time of segregation.

It sat on the pages of African American travel guides for a decade, and remained one of only three Colorado motels to be listed through 1967.

Nomination

The idea to nominate the Coronado Lodge to the National Register started in a movie theater.

Pueblo historian Corinne Koehler settled into her seat to watch “Green Book” — a 2018 movie about a Black pianist traveling across the South during segregation. That’s how she learned about the historic use of Black travel guides.

“Watching the movie, I’m kind of thinking, ‘Well that’s kind of interesting,’” Koehler said. “I never knew anything about the Green Book before, and I was kind of curious to see if there were any places in Colorado.”

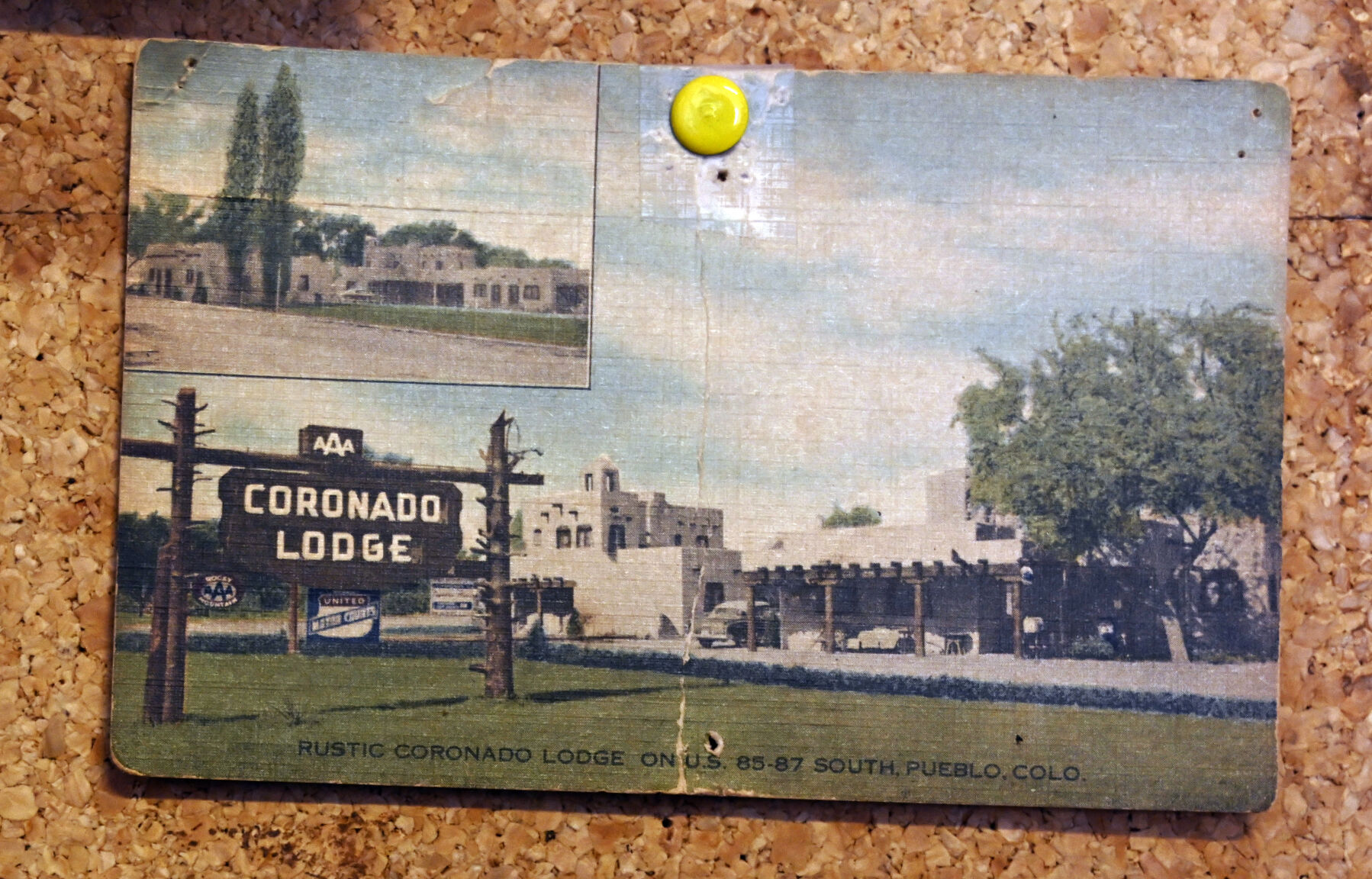

A vintage postcard shows what the Coronado Lodge looked like during a different era, very similar to the way it looks today. (Photo by Jerilee Bennett, The Gazette)

So, she began researching. Using the New York Public Library’s online collections, Koehler sifted through digitized Green Books.

“Sure enough, there were places — quite a few as matter of fact — listed in Pueblo, so that got my interest,” she said.

Many of the buildings listed in the books were no longer standing. Some were only listed once. But there was one that stood out to Koehler.

“I noticed the Coronado, and I was familiar with the Coronado Motel on Lake Avenue,” she said. “So, I contacted the owner.”

Koehler spoke with the motel’s owners, Shay and Atilano Perez, telling them about the history of the space and encouraging them to apply to the National Register.

So, with the help of historians Tom and Laurie Simmons of Front Range Research Associates, the group began to dive into the story of the Coronado in hopes of applying to the National Register.

History

The Coronado Lodge was built in 1941 by Scotland-born Ralph Ferris, making it part of the motel boom seen throughout the 1940s to 1960s across the U.S.

But, it didn’t stay in Ferris’ hands for long. The motor court was bought by the Copley family in 1946, who went on to run the motel for the next two decades, according to research by the Simmonses.

Artie and Hattie Copley expanded the motel during the first couple of years of owning it, adding two guestroom buildings. No large buildings have been added to the lot since 1948, and most of the U-shaped structure is still held together by the original adobe bricks made by a local brickmaker.

“It was a first-rate place,” Tom Simmons said. “If you look at some of those postcard views, it was really quite a nicely maintained and the design is actually a Pueblo Revival style motel. “

A seating area at the historic Coronado Motel shows the adobe style that makes the motel unique.

The motel’s location was also ideal for travelers, sitting on Lake Avenue — the original entryway into Pueblo, Tom Simmons said.

During its heyday, Lake Avenue was an entertainment strip, which could have attracted a lot of Black entertainers, Koehler said.

The Copleys welcomed Black travelers since acquiring the hotel in 1946.

“We didn’t discriminate about anybody. They had the money, they were welcome. … We didn’t turn anybody away,” Joyce Copley Reimer, the daughter of the Copleys, told the Simmonses during their research.

The listing was uncommon in the fact it was an established motel, as opposed to the more common “tourist homes” suggested for lodging, said Dexter Nelson II, History Colorado’s associate curator of Black history.

“It’s one of the shining examples of the motels back in the day that would have been safe space,” Nelson said. “It’s an interesting example of an actual motel as opposed to a house.”

While most business owners who listed their services in Green Books were Black or Jewish, the Copleys also stood out as white Methodists, Tom Simmons said.

“They apparently just had a feeling that if you had the wherewithal to pay for a room, you have a right to a room, so that was quite interesting,” he said.

Throughout the segregation era, the city of Pueblo maintained a variety of listings in Black travel guides.

Pueblo had a small but relatively significant African American population during the 20th century.

The Pueblo chapter of the NAACP was established back in 1918, said Roxana Mack, the current NAACP Pueblo president.

“A lot of Blacks had moved here for work at the steel mill, so there was a lot of activism at that time,” Mack said.

The city was also home to Colorado’s only known Black orphanage at the time: the Lincoln Home. Founded by the city’s Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, the orphanage served African American children, who were not accepted by the local Catholic orphanage, Nelson said.

“That was a really great history that we’re still very much uncovering and exploring today,” Nelson said.

Unfortunately, not much is known about who stayed at the motel, with old visitor logs trashed after the 1980 death of Floyd Christmas, who acquired the motel after the death of Artie Copley in 1966. Koehler estimates those records spanned decades.

“The basement was full of records and they just tossed it,” Koehler said. “Who knows how many he threw away, but from what you hear he was a real packrat. So I’m assuming they got everything since day one.”

Today

The Coronado Lodge, now called the Coronado Motel, now operates as an extended-stay motel, renting on a weekly basis. Shay and Atilano Perez purchased the motel about 30 years ago and have been running it since.

“Every room is unique,” Shay Atilano said.

Last February, during Black History Month, the Pueblo NAACP honored the Coronado with a plaque, thanking the motel for being a refuge for African American travelers during a time when many places would turn them away.

“We felt that it was important to recognize the significance of what they did during that period of time, knowing that it wasn’t a popular decision, but they felt that it was the right decision,” Mack said.

“It was an honor,” Shay Atilano said.

The Atilanos have built a collection of plaques since unearthing the motel’s history, one hanging near the entrance, that the Atilanos display front and center.

“This property has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the United States Department of the Interior,” it reads.

More Stories

Complete Guide To Exuma’s Hidden Gem

Birkenstock Sandals Are on Major Sale

Complete Guide To Austria’s Beautiful Capital City